FAMILY GROUP RECORD OF

JACOB MEE AND

CATHERINE ABBOTT

Jacob Mee was christened 22 July 1734

in Heanor, Derbyshire, England. He

was the son of Benjamin Mee and Rebecca Moore. Jacob married

Catherine Abbott 1 November 1756 in St. Alkmunds, Derbyshire.

Catherine was christened 2 December 1732 in Horsley,

Derbyshire, the daughter of John Abbott and Anne Shaw.

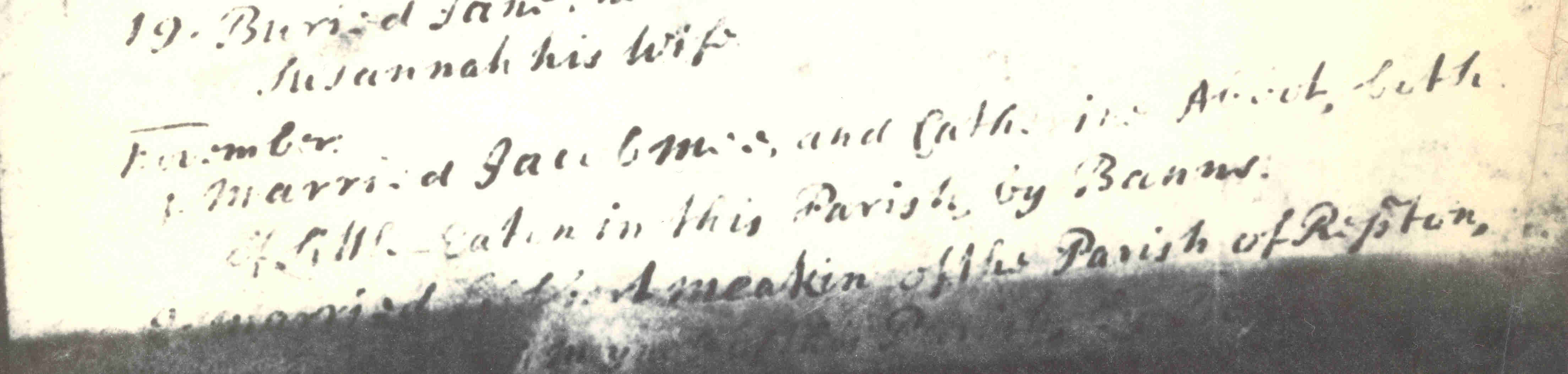

Marriage record

for Jacob Mee and Catherine Abbott - "Married Jacob Mee,

and Catherine Abbot, both of Little Eaton in this parish

by Banns",

St.

Alkmunds parish register.

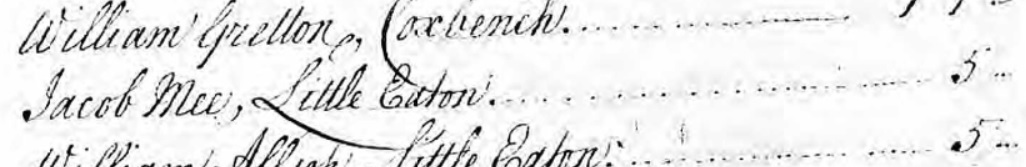

Jacob is found on a list of contributors for building a chapel in Little Eaton in 1790.

Catherine died and was buried 5 November 1796 in Little Eaton,

Derbyshire.

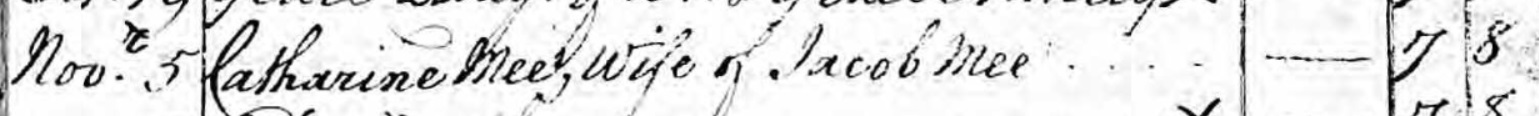

Burial record for Catherine Mee in Little Eaton:

"Nov 5 - Catharine Mee, wife of Jacob Mee"

Jacob died and was buried 29 May 1804

in Little Easton,

at the age of 70.

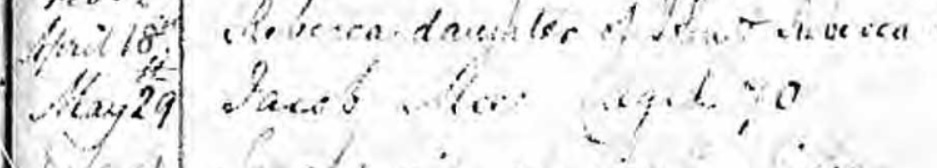

Burial record for Jacob Mee in Little Eaton:

"May 29th - Jacob Mee aged 70"

Jacob and Catherine had the following children:

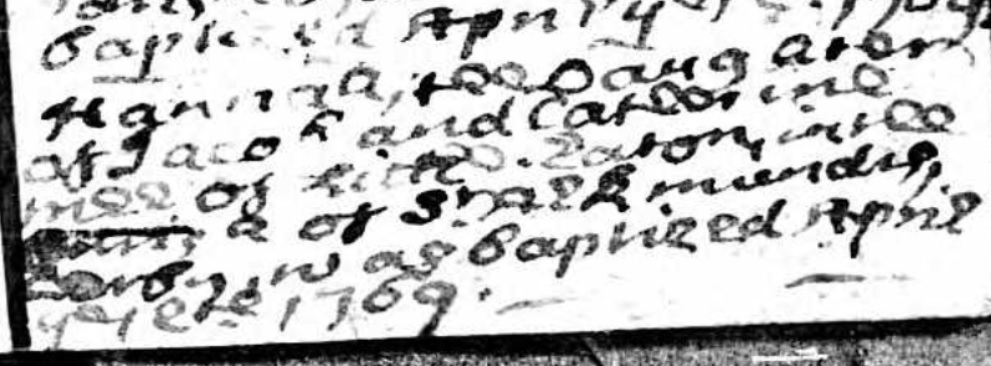

Baptism record for Hannah Mee in the Duffield Presbyterian church: "Hannah, the daughter of Jacob and Catherine Mee

of Little Eaton in the parish of St. Alkmundes, Derby, was baptized April ye 12th 1769"

FAMILY

GROUP RECORD OF

BENJAMIN

MEE AND

REBECCA MOORE

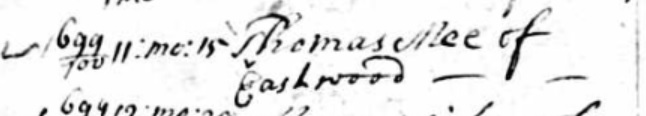

Benjamin Mee

was christened 20 September 1693 in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire,

the son of Thomas and Rebekah Mee. Eastwood is about nine

miles from Heanor. It is a village and parish in

Nottinghamshire on the border of Derbyshire. Eastwood was the

birthplace of D.H. Lawrence. There was a local coal mine, and

later stocking-making industry. Benjamin worked as a labourer.

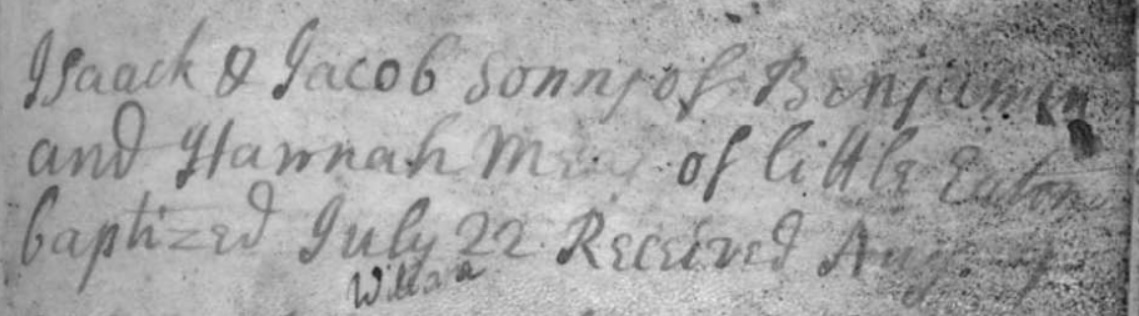

Benjamin and Hannah Mee had twin sons, Isaac and Jacob. Benjamin's name had been transcribed in the IGI as Canaman or Conan, however the original parish register for Heanor clearly shows his name as Benjamin. The parish register (FHL #2104171) says: "Isaack & Jacob sonns of Benjamin and Hannah Meas of Little Eaton baptized July 22".

Baptism record for Isaac and Jacob Mee in Heanor:

"Isaack & Jacob sonns of Benjamin and Hannah Meas of Little Eaton baptized July 22 Received Aug 4"

A marriage was recorded for Benjamin Mee of Eastwood and Rebekah Moore of Heanor on 30 April 1719 in South Wingfield, Derbyshire. Heanor and Eastwood are about two miles apart. Benjamin and Rebecca then had children: Elizabeth (christened 1719 in Eastwood), , Benjamin (1729 in Horsley, shown as "of Little Eaton"), John (1730 in St. Alkmunds, Derby), Joseph (1736 in St. Alkmunds, Derby), and Hannah (1738 of St. Alkmunds, Derby). A daughter, Rachel, of Benjamin and Rebecca was buried in 1737 in Eastwood, shown as "of Little Eaton". Rebekka Mee, the wife of Benjamin Mee "of Eton" died and was buried 6 February 1776 in St. Alkmunds, Derby.

Additionally, these children were christened in Horsley, Derbyshire, of Benjamin Mee, with no mother listed: Anna (1725 in Horsley, "of Little Eaton"), Josiah (1728 in Horsley, shown as "of Little Eaton"), and John (1731 in Horsley, "of Little Eaton"). Horsley is about two miles north of Little Eaton.

Was there more than one Benjamin Mee in Little Eaton? Or did the parish clerk erroneously record Hannah as the mother of Isaac and Jacob, instead of Rebecca? The answer is found in the will of Samuel Mee of Horsley, written in 1761. Samuel Mee of Kilbourn in the parish of Horsley, Derbyshire, milner left a will written 9 October 1761 and proven 7 November 1761. He left bequests to his six brothers and sister: "Also I give, devise and bequeath unto my six bredren Josiah, John, Benjamin, Isack, Jacob, Joseph Mee, and my sister Liddy the sum of seven pounds of lawfull British money." All the rest and residue was left to his wife Elizabeth Mee, who was also named executor. Samuel's bequest ties together Isaac and Jacob with the aboved named children for Benjamin and Rebecca, along with those only listed as Benjamin's children. (Note: Liddy is a nickname for Elizabeth). John of 1730, Hannah, Anna and Rachel were not mentioned in Samuel's will, and may have died before 1761.

Isaac and Jacob's mother Hannah was actually Rebecca. Rebecca was the daughter of Josiah and Rebecca Moore of Heanor. Josiah was a miller, and left a will dated 1721. Rebecca, his widow, left a will dated 1740. Both wills mentioned their daughter Rebecca Mee. (Lichfield and Coventry Wills, www.findmypast.co.uk)

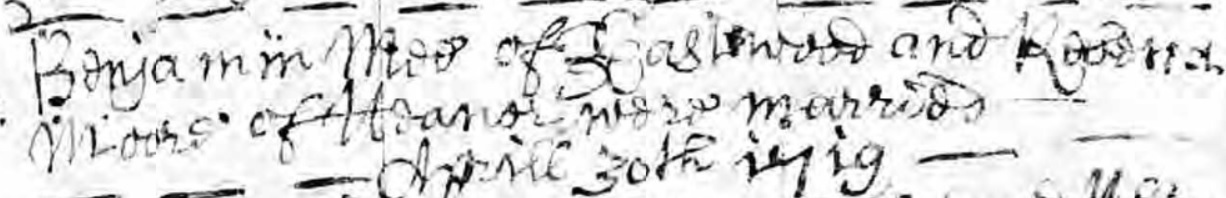

Benjamin Mee of Eastwood married Rebecca Moore of Heanor on 30 April 1719 in South Wingfield, Derbyshire.

Marriage record for Benjamin Mee and Rebecca Moore in South Wingfield:

"Benjamin Mee of Eastwood and Rebecca Moore of Heanor were married Aprill 30th 1719"

1. Elizabeth (Liddy), christened 24 June 1719 in Eastwood, Nottingham; mentioned in brother Samuel's will of 1761.

2. Samuel, born about 1721; married Elizabeth Langton 1 January 1744 in Morley, Derbyshire; died 1761, leaving a will.

3. Anna, christened 29 November 1725 in Horsley, Derbyshire, "of Little Eaton in the parish of St. Alkmunds, Derbie".

4. Josiah, christened 3 June 1728 in Horsley, "de Little Eaton"; married Mary Moore 18 May 1760 in Spondon, Derbyshire; mentioned in brother Samuel's will of 1761.

5. Benjamin, christened 17 February 1729 in Horsley "of Little Eaton"; mentioned in brother Samuel's will of 1761.

6. John, christened 20 November 1730 in St. Alkmunds, Derby.

7. John, christened 4 March 1731/2 in Horsley, "of Little Eaton"; married Hannah Garrott 1 June 1753 in Horsley; mentioned in brother Samuel's will of 1761.

*8. Jacob, christened 22 July 1734 in Heanor, Derbyshire, "of Little Eaton" (twin); married Catherine Abbott 1 November 1756 in St. Alkmunds, Derbyshire; mentioned in brother Samuel's will of 1761.

9. Isaac, christened 22 July 1734 in Heanor, Derbyshire, "of Little Eaton" (twin); mentioned in brother Samuel's will of 1761.

10. Joseph, christened 2 March 1736 in St. Alkmunds, Derby; married Jane Hibbart 25 July 1767 in Morley, Derbyshire; mentioned in brother Samuel's will of 1761.

11. Rachel, buried 1737 in Eastwood, "of Little Eaton".

12. Hannah, christened 29 December 1738 in St. Almunds, Derby.

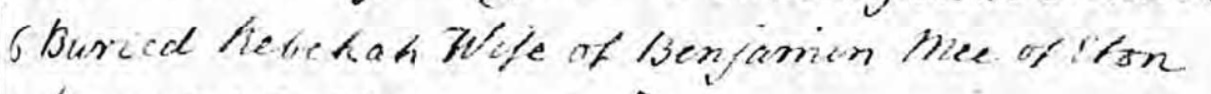

Rebecca died and was buried 6 February 1776 in St. Alkmunds, Derby:

Burial record for Rebecca Mee in St. Alkmunds, Derby:

"6 - Buried Rebekah wife of Benjamin Mee of Eton"

Benjamin Mee died and was buried 12 October 1779 in St. Alkmunds, Derby.

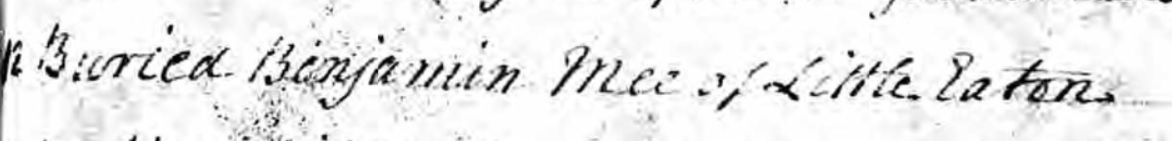

Burial record for Benjamin Mee in St. Alkmunds:

"Buried Benjamin Mee of Little Eaton"

THOMAS AND REBEKAH MEE

Thomas Mee was christened 27 February 1666 in Eastwood, the son of Thomas and Rachel Mee. He married Rebekah in about 1690. Thomas' occupation was laborer.

Rebecca died and was 5 September 1720 in Eastwood. Thomas died and was buried 16 November 1746 in Eastwood.

Thomas and Rebecca had the following children:

1. Ann, christened 3 July 1691 in Eastwood.

*2. Benjamin, christened 20 September 1693 in Eastwood; married Rebecca Moore 30 April 1719 in South Wingfield, Derbyshire; buried 12 October 1779 in St. Alkmunds, Derby.

3. Alice, born 25 December 1698 in Eastwood; christened 22 January 1699 in Eastwood; married Robert Flint 5 June 1723 in Ilkeston, Derbyshire; buried 1 March 1784 in Ilkeston.

4. Rachel, christened 5 March 1701 in Eastwood; daughter of Thomas "a labouring man"; buried 20 March 1702 in Eastwood.

5. Catherine, born 13 December 1704 in Eastwood: christened 14 December 1704 in Eastwood; married Robert Howet 18 May 1731 in Eastwood; buried 27 April 1742.

6. Esther, born 2 April 1707; christened 6 April 1707 in Eastwood; buried 5 April 1710 in Eastwood.

7. Hannah, christened 20 February 1708 in Eastwood; married Samuel Stanerod.

8. Thomas, born about 1711 of Eastwood; buried 6 April 1715 in Eastwood.

9. Esther, born 5 November 1715 in Eastwood.

SOURCES: Horsley parish register; Eastwood Bishop's Transcripts; www.familysearch.org.

THOMAS AND RACHEL MEE

Thomas Mee was christened 23 March 1632 in Eastwood, the son of Laurence and Susanna Mee. He married Rachel. His occupation was laborer.

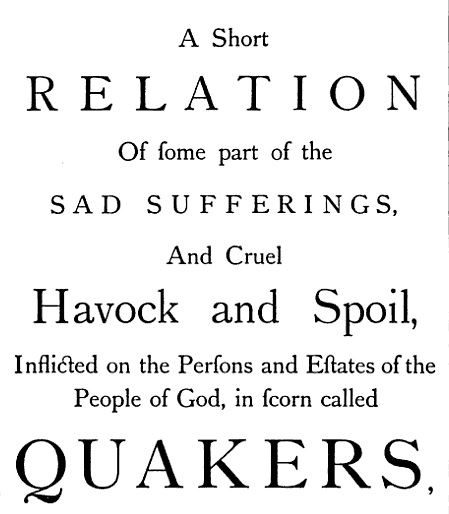

Thomas and his father were Quakers. "The Mee family during that period were Quakers and a large group of Quakers were well established in the geographical triangle formed between Nottingham, Derby and Mansfield. In 1689 Lawrence and Thomas Mee were allowed to affirm instead of taking the oath of allegiance. Thomas was brought before the church court for failing to attend divine service for four consecutive weeks." (Researcher Ray Marsden) About forty Quakers were reported to be in Eastwood in 1669.

From The Sufferings of the Quakers in Nottinghamshire, 1649-1689: In 1676, Thomas Mee testified in court in behalf of William Day of Newmenleas near Eastwood who was fined for preaching.

The Toleration Act of 1689 allowed the Quakers in England to affirm instead of taking the oath and the following made Statutory Declaration:

Eastwood - Elis. England, Willm. Day, Jos. Potter, Lawr. Mee and Thom. Mee

(Extracted from the Book - Nottinghamshire County Record - 17th entury)

Thomas died 15 January 1699. His burial record is found in the Monthly Meeting of Chesterfield Quaker records.

Death record for Thomas Mee of Eastwood in the Monthly Meeting of Chesterfield Quaker Records

Rachel died and was buried 20 March 1708 in Eastwood. Her occupation was shown as thatcher.

Thomas and Rachel had the following children:

1. Prudence, christened 27 February 1666 in Eastwood (twin); buried 3 March 1666 in Eastwood.

2. Thomas, christened 27 February 1666 in Eastwood (twin); married Rebecca; buried 16 November 1746 in Eastwood.

3. Elizabeth, christened 18 November 1668 in Eastwood; not married.

SOURCES: Horsley parish register; Eastwood Bishop's Transcripts; www.familysearch.org; e-mail from Ray Marsden; The Sufferings of the Quakers in Nottinghamshire, 1649-1689; Monthly Meeting of Chesterfield Quaker records on www.ancestry.co.uk..

LAURENCE AND SUSANNA MEE

Laurence Mee was born about 1600 of Eastwood. He married Susanna. Laurence was a Quaker. Susanna died and was buried 27 March 1668 in Eastwood.

Laurence and Susanna had the following children:

1. Thomas, christened 23 March 1632 in Eastwood; married Rachel.

2. Francis, christened January 1634; buried 8 January 1634 in Eastwood.

3. Prudance, christened 28 May 1636 in Eastwood.

SOURCES: www.familysearch.org; Eastwood Bishop's Transcripts.

Quakers in Nottinghamshire

"The early Quaker movement tended to be centred in the north of the county of Nottinghamshire, around Mansfield...The beginnings of the Quaker movement can be directly ascribed to one man, namely George Fox who was born in 1624 at Drayton-in-the-Clay, Leicestershire where he was an apprentice shoemaker. George took to ‘wandering’ around the Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire countryside in his search for God whilst at the same time trying to convert the local populace to his way of thinking. It was on one of these ‘wanderings’ that George visited a meeting at Broughton, (it is unclear whether or not it was Nether Broughton or Upper Broughton), of Baptist Separatists, who were also known as ‘Shattered’ Baptists. At this meeting George had a vision of ‘The Inner Light’ that he believed was a divine spark of light which was from God and was to be found in every person. This Inner Light made all men equal before God and their lives were likewise precious. This was very radical for 17th century England. Certainly the established church would not agree with such sentiments.

Fired with that zeal that is the mark of the zealot George began his crusade to help others to discover their ‘Inner Light’. So it was that in the 1640’s he settled in Mansfield and was soon recruiting members to his new creed. It was in Mansfield that George made his first converts...From Mansfield George spread his message and gained followers throughout the country as further people were converted to the creed.

In 1676 a survey was undertaken by the Anglican Church to identify how many papists and ‘dissenters’ were sheltering in each parish. The incumbents in each parish were required to compile a register of all such persons...As is usual with radical thinkers like George it wasn’t too long before he was in trouble with the authorities, which in his case was the Anglican Church. George took it upon himself to enter churches whilst services were being taken and disrupt the service by proclaiming to the assembled congregation that what they were doing was wrong, indeed even heathen. According to George there was no need for services to be conducted in grand buildings, which were expensive to build and maintain. Neither was it necessary to follow a strict theology laid down by a non-representative ruling body, or be compelled to pay tithes to that body. In George’s eyes there was no need for a priest to intercede between a person and God, the individual could communicate directly with God himself via his ‘Inner Light’. Unsurprisingly this sort of behaviour often led to trouble both from the church authorities and also the church congregation. It was even not unknown for him to be attacked by a hostile group of churchgoers.

Disrupting church services was a criminal offence so it wasn’t long before George found himself in front of the local magistrates...All of this was occurring with the English Civil War as a backdrop. Nottingham had strong Royalist sympathies and persons like George, who were rocking the proverbial boat, with their perceived anti-royalist views were not looked on kindly.

Jail in no way dampened George’s religious ardour. Upon the completion of his sentence, which entailed several months in jail, George returned to Mansfield where he was soon back to disrupting church services. From Mansfield George then travelled across the county border to the town of Derby, where he was once again in trouble with the law for creating yet another disturbance in a church. The year was 1650 and this brush with the law led to a legendary episode. Whether or not it is absolutely true is debatable but the story goes that Fox found himself once again before the bench. The result was that George was imprisoned after being found guilty of blasphemy. George told by Justice Bennett, the judge who sentenced him, that he ought to ‘tremble at the word of the Lord, whereupon the judge called George a ‘Quaker’ as a term of derision. Far from being insulted George took to the term and thereafter wore the name ‘Quaker’ much like a badge of honour. From thenceforth adherents of the cause were known as ‘Quakers’.

George Fox continued on his ‘wanderings’, trying to bring enlightenment to other souls, often succeeding and often finding himself inside jail again for his troubles. Indeed, there were very few years during the 1650’s when George didn’t enjoy a spell of imprisonment at some time or another in some English town or city’s jail. Nevertheless the Quaker movement flourished, thousands were converted to George Fox’s religious views. Indeed, such were the numbers being recruited into the creed that that period of time was christened the ‘Quaker Explosion’. Equally a great many of them found themselves imprisoned for their beliefs. At one time there were around a thousand Quakers in jails up and down the country. Many also had to pay swingeing fines that left them all but destitute. The authorities were exceptionally hostile towards the movement, fearing, not unnaturally, that if the movement managed to get itself seriously established then it would pose a very real threat to the established church and government.

It was as a result of all these brushes with the law that George developed a loathing for oaths. The law of the land dictated that all of the monarch’s subjects swear an oath of allegiance towards the crown. Likewise, in court evidence was given under oath. George refused to do either, indeed the refusal to swear an oath of any kind became one of the tenets of the Quaker movement. Another binding principle of the movement was that no Quaker would take up arms against another man. At a time when the country was riven by civil war this was a radical concept.

Whilst the Quaker movement had no established theology it did have a set of basic tenets, some of which are the following: -

1. An opposition to steeple-houses and the hireling priesthood. ((Since church buildings and other ‘houses of God’ were anathema to them Quakers held their meetings wherever it was convenient to do so. It may have been at a Quaker’s house or it may have been at a property specifically acquired for the purpose. There was no formal order of service. Each Quaker communed with God in whatever way suited them. Perhaps someone might offer a prayer to God or the meeting might be conducted in total silence as each Quaker communed with God via his or her Inner Light.)

2. A refusal to pay tithes and church rates.

3. Hat honour. (Quakers all wore similar hats and refused to take them off as a sign of respect for someone deemed to be their social superior.)

4. The use of the second person singular; i.e. persons were referred to as ‘thee’ and ‘thou’.

5. The use of the first day and first month. The names of the days and months were deemed to have heathen or pagan origins and thus, not to be used. Therefore both days and months were simply numbers; i.e. January in month one, February month two and March month three etc. Thus July 12th would be referred to as day 12 of the seventh month.

6. The refusal to be married or buried in church property.

7. The refusal to take oaths.

8. Pacifism, although this became commonplace after the end of the Civil War.

9. Simplicity of dress.

Because of their beliefs Quakers were in constant danger of falling foul of the law of the land. The penalties that were imposed by the State when the law was broken verged on the Draconian. To live the life of a devout Quaker called for a considerable degree of fortitude and determination. The tribulations that were visited upon the Quaker movement because of their faith were called ‘sufferings’. These ‘sufferings’ were recorded in the form of pamphlets and other literature and these were distributed amongst the followers, hopefully giving them strength and courage to pursue their religious calling.

One way in which the State attempted to combat the perceived threat that Quakerism posed was by imposing laws specifically aimed against the movement. In this respect a whole raft of laws were introduced, covering all manner of offences from alleged treason at one end to meeting illegally at the other. The penalties for transgressing these new laws could very severe, ranging from transportation, imprisonment and fines. Quaker meeting were open to all so it was a simple matter for the powers that be to send a spy along to any meeting and then inform the authorities of any wrongdoing. Informants were often entitled to a reward so there was never a shortage of willing informants. The most common punishment for any lawbreaking was a fine, If the fine could not be paid then goods and chattels were taken in lieu. This had the effect of causing great financial hardship to many of the followers. It was not unknown for a Quaker to be reduced to the level of a pauper. By and large though such laws rarely have the desired effect and the Quaker movement continued to thrive. As time progressed so many of these laws fell into disrepute. It was seen that they were manifestly unfair and they were not having the desired effect. Many judges and jurors began to be sympathetic to the Quakers and the law began to be implemented with less vigour. Reducing Quakers to paupers merely placed a financial burden on the local parishes and this was in nobody’s best interest.

By the time that George died the laws against groups such as the Quakers had been greatly relaxed. Indeed the Act of Toleration, which was passed in 1689 (two years before George's death) effectively ended the state persecution of Quakers."

(A Persecuted People - Early Quakers in Nottinghamshire; Derek Walker; http://www.keyworth-history.org.uk/about/reports/0804.html)

(From The Sufferings of the Quakers in Nottinghamshire, 1649-1689, published 1690)