Jim and his mother Mary

EARLY YEARS

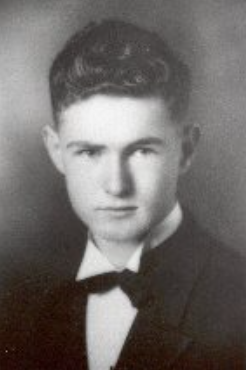

James

Aloysius Carey was born February 7, 1920 in San Francisco,

California. His parents, John Joseph Carey and Mary Josephine

Hickey were the children of Irish immigrants who settled in

Chicago. Jim was named James for his father's older brother,

and Aloysius for the Catholic parish in Chicago where his

parents married. He remembered, "That's where my name came

from ‑ my Mom and Dad were in St. Aloysius parish when

they were married."

Jim's

father worked as a credit manager for the City of Paris

department store in San Francisco. His mother was very active

in the Catholic Daughters organization, and later in the

Berkeley City Women's Club.

Jim's

two older brothers, John, age 9, and Tom, age 7, had been both

born in Chicago. The age difference between Jim and his two

older brothers helped develop a quiet independence in Jim.

In a

taped interview in 1982, Jim remembered, "My earliest

recollection of anything is in about 1924 or 5. I remember the

Dole Pineapple Air Race from Oakland to Hawaii. I lived two

years in San Francisco, then moved to Berkeley, to 1427

Berkeley Way." Jim had no remembrance of his grandparents, as

they had died before his birth, or when he was very young. He

did remember, "In 1926, my Mother and myself, and my two

brothers, went back to Chicago for Grandma Hickey's funeral. I

was about six years old."

Some of

Jim's childhood memories were of going to the City of Paris

store and watching the trains run in the toy department while

his mother shopped. The family also went to the City of Paris

store at Christmas time to see the beautifully decorated tall

Christmas tree displayed there every year. The Carey family

Christmas was organized by Jim's mother. When the boys went to

bed on Christmas Eve, there were no signs of Christmas. That

night their mother would bring home a Christmas tree and

decorate it. When the boys woke up in the morning they would

find a fully decorated tree, complete with presents under it,

had magically appeared in the living room. One Carey family

tradition which continues to this day is the lavish use of

carefully hung icicles.

The

family next moved to 307 Rugby Avenue in Berkeley. Jim

attended St. Joseph's parochial school, where he met Ray

Hammons, his childhood best friend. They used to play across

the street in a vacant lot, and dig trenches there.

Jim's

father let him have a chemistry lab in the basement. Jim's

friends would encourage him to do chemistry experiments, like

making paint or exploding cans. He recalled, "We used to stick

sodium out on the street, and turn water on it. It would go

off with a big flash."

Jim was

a good student, with a great love of learning and reading. His

room had two beds, one of which was kept piled with books. His

mother wouldn't let the cleaning woman disturb Jim's books.

His mother was somewhat protective of her youngest child. He

achieved the rank of Eagle Scout. His father loved building

crystal radios, and Jim remembered that his Dad was always

building a bigger and better one. Jim recalled, "He was

building radios before they had networks - they just had a

little local station in San Francisco, and he built radios for

about three or four years, and I just naturally got into it

after that - mostly fixing the ones he built, I guess."

Jim

worked part time while in college as a courier for the credit

bureau where his brother Tom worked. His job was to walk

reports across Oakland. They liked him because he walked fast.

Next he worked from January 1939 to January 1942 as a

bookkeeper for the Bank of America. Among his group of

Catholic school friends, which included Ray Hammons, and Ray's

future wife, Patricia, was a girl whose father worked for the

Bank of America. One day her father asked Jim if he'd like to

work for the Bank of America. He said, "Sure.", not knowing

that a 42 year career was beginning. Jim attended UC Berkeley

until World War II broke out.

WAR YEARS

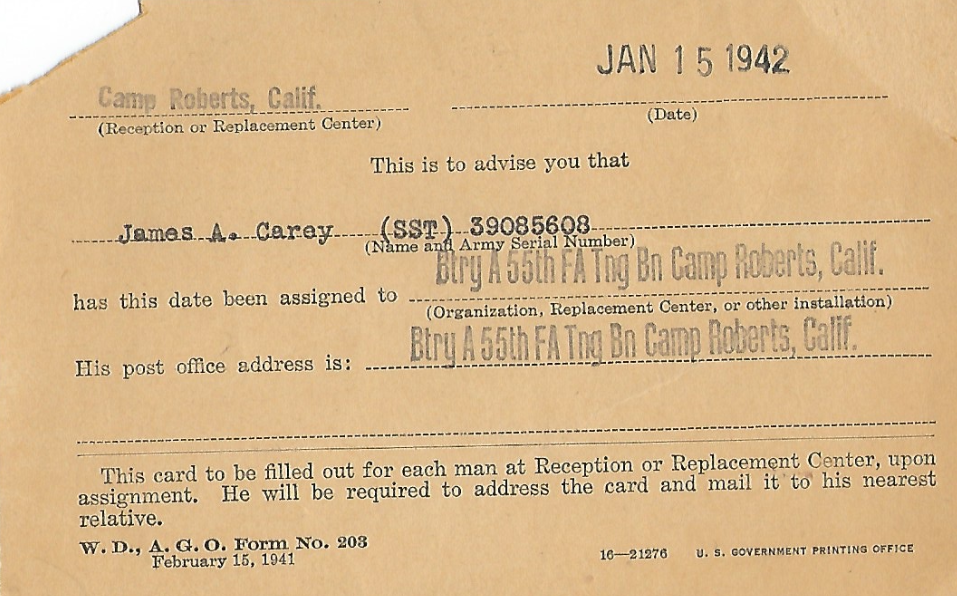

After

Pearl Harbor, the sheltered, intelligent 22 year-old college

student from Berkeley went to war. Jim never expected to come

back. His parents also expected that he would not return from

the war. Jim received his notice of selection on December 17,

1941. He was ordered to report for training to the Presidio at

Monterey on January 9, 1942.

Six days

later he was sent to Camp Roberts for Desert Warfare training.

Here he "met" the legendary General Patton. Jim was driving a

jeep which broke down at an intersection. General Patton's

jeep pulled up to the intersection. General Patton stood up in

the back of the jeep and told Jim to "get that #@!*#! jeep out

of here!" Jim remembers staring at General Patton's

pearl-handled revolvers. He followed General Patton's orders

as fast as he could.

Jim

completed his basic training for Field Artillery in April.

Private James Carey was assigned to Battery B of the 49th

Field Artillery Battalion. In June he was promoted to Corporal

at Camp San Luis Obispo. In July he became a Sergeant, and in

September he was promoted to Staff Sergeant in the 7th

Division under the command of General Joseph Stilwell, also

known as "Vinegar Joe".

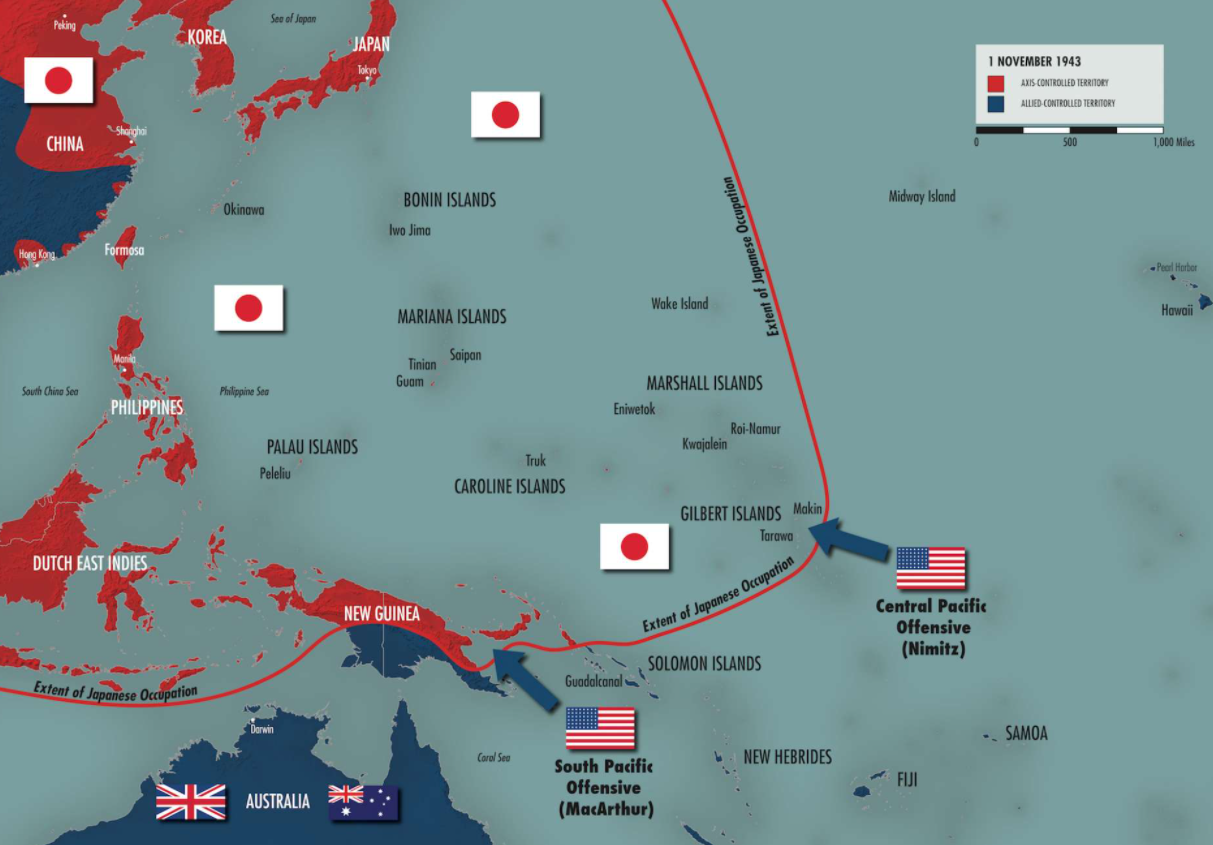

After extensive training in desert warfare for use in Africa,

they were sent to the Pacific to fight the Japanese. In April

of 1943, they sailed for the Pacific under the command of

General Albert E. Brown.

In a

book entitled "The 7th Did It the Hard Way" the history

of the 7th Division is told: "They hurriedly traded desert

clothing for arctic woolens and heavy leather boots. Though

trained for tropical warfare they had to be rushed to the

Arctic, because in those grim days of too little and too late,

they were the only troops we had ready." The ships sailed to

bleak Cold Bay, Alaska, where one of the Navy's first shore

bombardment fleets of old battleships and destroyers was

gathering."

Jim's

experience in the Aleutians was miserable. He almost froze to

death, and got blood poisoning from a cut. The history

continues, "The division attacked Attu on May 11, 1943. Attu

was a fog-shrouded nightmare. Streams howled from the treeless

mountains down to the barren black beaches. For eleven days

some units waded through the ankle-deep, sticky mud. Almost

every hour, bullets and shells whistled over them, but in all

that time they saw no enemy soldier alive. There was no food

shortage on Attu the first night. After 36 hours, the division

barely had a foothold in Massacre Valley. Those 36 hours, and

the remainder of the 21 days of the Attu battle were endless

successions of treacherous climbs up icy mountainsides, of

sleeping in water-filled fox holes, feet swelling until boots

had to be cut away, sleeplessness, cold, misery from soaked

clothing and worn-out socks, frosted fingers, and rusted

weapons. The enemy fired from the fog, fell back, and fired

from the fog again."

At home

in Berkeley, Jim's mother and father worried about him. His

mother mailed him envelopes of Shredded Wheat, and other

cereals to keep him from starving. A baby boy born to Jim's

older brother John was named James in his honor.

Jim was

a artillery spotter, going in front of the front lines, and

calling down fire on enemy guns. This was an extremely

dangerous job. Jim's friend, Jerry Smith remembered with

admiration the calm voices of the artillery spotters,

directing fire as bombs exploded around them. In addition to

these duties, Jim and the other soldiers had the unpleasant

responsibility of burying dead Japanese soldiers in the frozen

tundra. The 7th Division "spent weary months cleaning up

battle debris, building bases, and burying the frozen dead in

the Attu mountains. All summer it dug Japanese stragglers out

of the caves and snowbanks, and guarded against their raids on

American supplies." When the Japanese soldiers saw that the

battle was lost, they committed suicide rather than be taken.

None survived the battle of Attu.

The

history continues: "Then the division reboarded its ancient

transports and went to Hawaii." The division rested and

received training in jungle warfare.

In

January 1944, they sailed for Kwajalein, in the Philippines,

and arrived there on February 1. "Boiling hot, Kwajalein was

only a little more that two miles long, a fourth as wide. Some

5,500 Japs were crowded on it, with defense works covering

every usable foot. At first no direct attack was made on

Kwajalein Island. Instead, small forces went ashore on

undefended Enubuj, two miles up the lagoon. There the division

artillery set up sixty guns, hub to hub, on the tiny islet.

While battleships offshore hurled in 16-inch shells, these

guns methodically pulverized the northwest end of Kwajalein,

until no blade of grass remained, then two regiments stormed

the beach. Five days later it was all over." Photos Jim took

show the enormous destruction.

"Fuel Tanks - Enibuij"

(Photo by Jim

Carey)

"Oil fires

behind Japanese

line - Kwajalein" (Photo by Jim

Carey)

"Power Station - Enibuij Is" (Photo by Jim Carey)

Once

again, burial duty was an unpleasant responsibility for Jim

and the other soldiers. The 7th Division again returned to

Hawaii.

Seven

months later, in September of 1944, the 7th Division was at

sea again. Its orders were changed as they sailed, and they

were assigned to the Leyte assault forces in the Philippines.

This was to be the most memorable battle of Jim's service. An

article in the Field Artillery Journal, April 1945, entitled

"Fifteen Days - The Defense of Damulaan" was kept by Jim, with

handwritten notes in the margins of the article. These

handwritten notes are included here in italics.

"Damulaan

was a small town on the western coast of Leyte in the

Philippines. The island was dominated by jungle-covered,

precipitous ranges, broad, swift rivers, sweeping, rice

paddy-filled plains, and a solid perimeter of perfect landing

beach. Initial landing in Leyte Valley shattered the Imperial

16th Division, the barbarians of Bataan's Death March, and

forced them to set up delaying defenses in the mountains."

Jim's Battery was involved in building more than fifty bridges

over narrow footpaths into the mountains. The winter rains

caused hardships, washing out most of the bridges so

laboriously built. Food shortages were common. The only

defensive position was at Damulaan, 17 miles north. On the

15th of November, Jim and the Baker Battery were sent north.

"Heavy

rain had fallen the night before Baker Battery headed north,

and it was able to make only half the distance to the

objective by nightfall. By early afternoon of the 16th, it was

in position, however, just south of the Bucan River. By

nightfall defensive fires had ben registered. Baker, with one

platoon of infantry attached to it, formed the right flank and

rear of the front line. The audacious little force had needled

the hide of the enemy and was now prepared to resist to the

limit of its powers. The defense of Damulaan had begun."

The next

morning was bright and sunny. Escaping natives warned of a

large mass of Japanese forces moving toward them. The Baker

Battery had done an excellent job of camouflage of its

position, and were not spotted by enemy bombers. No action

took place that night except for a few short fire fights. For

the next several days the Battery waited, trying to conserve

ammunition and supplies.

"By the

20th it was apparent that we were facing a large enemy force.

Conservative estimates indicated that at least 3,000 Japanese

troops were concentrating on the high ground to our front and

right flank. At our Observation Post (underlined)

the observers could look across the 600 yards-wide valley and

see the enemy constructing trenches, machine gun pits, and OPs

on the opposite ridge."

"The day

of the 23d had been quite peaceful. At 18:30 the Jap's

artillery went into action for the first time. As all contact

with our forward observers attached to the company was lost (handwritten notes -

B-1, Lt. Reardon, Carey, Keith, Patterson, Kruse, Kussels)

no fire could be placed on the invaders."

Jerry

Smith, Jim's friend, recalls Jim telling him about the battle:

"On Leyte, there was an artillery unit that had gone into a

little town called Damulaan, and there was supposed to be

infantry out in front of them, and there weren't. Somehow or

another they got separated from their infantry unit that was

supposed to be out in front of the artillery. The artillery

actually found themselves on the front line. Of course, Jim,

as a forward observer, was out in front of them, observing

artillery fire. The Japanese made a big charge, and completely

overran the position. Jim and another fellow were in a foxhole

up there spotting artillery. They were completely surrounded

by the Japanese. They were overrun in the charge, and there

was a Japanese officer up on top of the foxhole swinging a

samurai sword at them. He actually glanced off Jim's helmet.

He fired his carbine at the guy, and they got out of it. The

Japanese disappeared - they got artillery support. They, in

effect, called the artillery fire almost onto their own

position."

The

article continued the story: "Our forward observer section (B-1)

returned with all hands uninjured and accounted for except the

officer, who had told the section to return and had gone back

into the melee to assist some infantry men in rescuing a heavy

machine gun. At noon the officer (Reardon)

who had been with the company that had withdrawn during the

night reported into our CP. He had spent the night entirely

isolated from our own troops. The men he brought back with him

reduced the missing to less than a dozen."

On the

26th at about 04:00 Baker Battery was attacked. A suicide

party of eight Japanese soldiers attacked. "A wild, almost

hand-to-hand, melee erupted. A hot grenade battle followed.

One man (Joseph),

further removed from the rest, did use his carbine, and was

immediately spotted by the enemy, who killed him with a

grenade after he had emptied his clips. The explosions of

grenades grew to a roar as the Japs repeatedly attempted to

scale the three-foot bank on which the guns were in position.

Finally one made it, and was promptly killed beside the trail

of the first piece by the chief of the adjacent gun section

(Lenz)."

"The

next day was spent as the last few had been. Again our

observers and air spotters hammered away at all types of enemy

installations and personnel. By the night of December 1st it

was possible for us to place a simultaneous barrage around the

three land sides of our perimeter. The fifteen days at

Damulaan were ended. Infantry guts and artillery skill

together had held the sector."

It was

here in the Philippines that Jim disarmed a Japanese officer,

taking his gun as a souvenir. The gun, a 1922 Browning 380

automatic, had the words in Ukrainian "Freedom Country"

engraved on the side. A gun expert speculated that the gun was

used by Ukrainian freedom fighters opposing the Communist

takeover. When the Communists succeeded, the Ukrainian freedom

fighters were pushed into China, and then into Japan. It was

there that the Japanese officer must have purchased the gun. A

weapon of this kind was considered a sign of rank in the

Japanese army. Jim brought it home from the war as a memento

of his experiences.

The 7th

Division rested only four days before proceeding to Okinawa.

There, according to "The 7th Did It the Hard Way" they

found that "the combination of hills, gullies, and cave tombs

could not have been better arranged for defense." Fred Lewis,

a fellow soldier said that Jim saved his life. They were in

the catacombs hunting down the Japanese. One jumped out and

was going to shoot Fred. Jim shot and killed the Japanese

soldier. Fred was grateful to Jim all his life.

It was

here in Okinawa that Jim received his Bronze Star for bravery.

With typical humility, he said it was for "working hard." For

a while the 7th's percentage of combat fatigue and shock cases

increased alarmingly, as men learned what it meant to fight

all day and to be shelled all night. The 7th Division spent

the next few months driving wedges into the enemy lines.

The 7th

Division was scheduled to be in the second wave of the assault

on Japan. Heavy casualties were expected. This became

unnecessary when Hiroshima was bombed, and the Japanese

surrendered. The war was over!

Jim had

enough service points to be eligible for discharge, and he

waited for his turn to go home. Jim's division had been

greatly reduced - only 20% had survived. He was given an

honorable discharge on October 17, 1945, and returned home to

a grateful country. The three years, nine months, and eight

days of war had been a memorable and frightening experience

for Jim. For years later he would sometimes wake up screaming

at night, as he relived painful memories. "After Attu, some

chair-borne columnist in this country said learnedly that the

soldiers of the 7th were so hardened that the Army was afraid

to turn them loose in the States again. That is just funny

now. Toward the end, men of the 7th had seen so much fighting

that they no longer bothered to pick up souvenirs. They

experienced so much of the real thing that they looked on

loud, tough-acting soldiers as pretty sad novices. When they

come home you will find them old field soldiers, quiet men

with a certain look in their eyes and a tightness around the

mouth, men who can't be pushed around and have no desire to

push anyone else around." (The 7th Did It the Hard Way)

WORK AND FAMILY

Jim

returned home to Berkeley, a few years older, with a changed

view of the world. He said what he missed most, other than

family, was fresh food - meat, fruit, and vegetables. When

asked what he learned from the war, he laughed and said,

"Don't volunteer for anything!" Things had changed at home,

too. Jim returned to work at the South Berkeley branch of the

Bank of America. He met and became close friends with Jerry

Smith, a Navy veteran who had also served in the Pacific.

In 1947

Jim met Beulah Green, a traveling secretary for the Bank. She

remembers their first meeting, " I was the traveling secretary

for all eighteen branches, and I went to South Berkeley. They

introduced me to all these guys and gals - the tellers, and

they introduced me to Jim. He said hello, and turned back and

finished his work. I thought, well that's a happy married man

with about three kids!"

They

dated for about a year, and then Jim asked Beulah to marry

him. Beulah said, "I told him I was going back to Salt Lake,

and he said, No, you can't." They were married August 20, 1950

at St. Joseph's Church in Berkeley, and then had their

reception at the LDS Institute on LeConte Street. They young

couple moved into the upstairs of a new fourplex at 344 Key

Blvd. in El Cerrito. They stayed there for a few months, then

moved into a duplex. Next they moved to a house on Liberty in

El Cerrito, where their son, Charles Joseph was born. Jim took

a sample of Charlie's baby hair, and checked it under a

microscope to see if it would be straight or curly.

3 1/2

years later a daughter, Alice Anne, was born. Thirteen months

later, another son, Raymond Patrick, was born. Raymond came

into the world on Jim's birthday. Beulah went into labor, and

made it into the car, when it became apparent that birth was

imminent. Jim delivered the baby boy, and then carried the

mother and child back into the house. Jim called the doctor,

who asked if Jim would like to cut the cord, or wait for her

to do it. Jim opted to wait. Beulah remembers that Jim's face

was a pale shade of beige!

In 1953 Jim had been

promoted to Assistant Cashier at the South Berkeley branch,

and was pleased at his position as a bank officer. It was a

shock when he was called to a meeting, and told that he had

been selected to work on the bank's new computer system, ERMA.

Other members of the ERMA team had these comments: "We were

accepted into the very first ERMA program, and we had no idea

what it was."; "I'd never heard the word computer before I got

into the computer department."; "I said I'm going to be a

programmer, and they said what is that?, and I said I don't

know either, and there we were!". At that time there were less

than 500 computers in the world. Banks were being drowned in a

sea of checks and deposit slips. In 1955 Bank of America

worked with Stanford Research Institute to create a prototype

check processing computer to handle all this paper. They used

Magnetic Ink Character Recognition, or MICR, which allowed the

numbers on the bottom of checks to be read by machines. ERMA,

or Electronic Recording Method of Accounting, was born. In

1957 General Electric signed a contract to build thirty ERMA

computers for the Bank of America. The members of the ERMA

team were amazed that the instruction manual was only 26 pages

long. They spent long hours redesigning the ERMA system. In

1959 the completed system was unveiled in a televised press

conference, hosted by Ronald Reagan.

ERMA

worked in this way: The ERMA process began in the branch,

where staff encoded each check with the dollar amount. Then

the checks were sent to the ERMA center. Checks and deposit

slips were put through ERMA's sorter/readers, which read the

micro-encoded information, and sorted the items by account

number. ERMA's computer them posted the accounts. All account

information was stored on magnetic tape. High speed printers

produced reports for the branches, and monthly statements for

customers. The improvement in paper handling was tremendous. A

competent bookkeeper could post 250 accounts per hour. ERMA

could post 550 accounts per minute.

Tony

Russo, Jim's boss, remembers the first meeting of the ERMA

team. They sat down, and Jim pulled a slide rule out of his

briefcase, and Tony thought, "I've got to compete with him!?"

Many members of the team were nervous about this new step in

their careers. Tony recalled, "When I first saw the computer

my first instinct was to turn around and run like heck back to

where I came from. But then I looked around the room, and saw

the other operations officers that I had worked with in other

branches, and I thought, heck, if they can do it, I can do it.

So I stuck around, and I became a programmer. I think the

early days of the ERMA system were very exciting. Everyone

realized that they had a chance to be creative. Most of us

were branch operations officers, and we knew the frustrations

of our people in the branches. We were virtually turned loose.

We taught each other programming. We worked together on each

other's programs. There was a good sense of camaraderie. We

accepted this challenge to do a good job for the bank, and to

make the job much easier for our colleagues. It was a real

challenge that we all relished. We put in 18, 20, 30 hour

days."

Things

did not always run smoothly. Tony said, "The checks passed

over this wire. The wire guillotined them right across the

middle horizontally, and all the bottom halves went into the

pocket. All the top halves went flying across the room. So we

had to get the scotch tape out, and here were all these

bankers, on hands and knees on the floor, scotch taping the

tops and bottoms of all these checks to get them back together

again."

An

engineer from Stanford stated this about ERMA, "This was the

absolute beginning of the mechanization of business. That was

the breakpoint. It was not only a great thing for the bank, it

unloosed automation." ERMA was so successful that within a

decade 90% of all banks were using similar equipment. "Thanks

to the vision, the courage, and the perseverance of a few

dedicated pioneers the age of computerized banking had begun."

Jim was one of those pioneers. He developed a real talent for

programming. His daughter, Alice, remembers when she was a

teenager, and Jim help her solve a problem by flowcharting it.

One of the ways Jim coped

with the pressures and long hours of work was by taking short

naps. Colleagues remembered him eating his traditional peanut

butter sandwich (with no jelly) for lunch, and then taking a

fifteen minute nap, then waking up refreshed and ready to

work. His son Raymond drew pictures of his family, showing his

dad stretched out on the his bed, taking his usual after-work

nap. Co-workers remembered that when they stopped off at the

bar for a drink after work, Jim would say, "No thanks, I've

got to get home to my family."

Family

life was sometimes exciting, too. In 1958 Pleasant Hill was

flooded, and the Careys had to leave their home. Jim carried

Alice out, and the family stayed overnight on the second floor

of the grocery store next door.

In 1961

Jim was saddened by the death of his father. John J. Carey was

83 years old. Jim recalled, "It was hard to watch him get

older. He was always so funny. Those last few years he wasn't

funny any more."

Jim's

young family was growing. Charlie's earliest memories of his

Dad were of piggyback rides down the hall to bed. Charlie

recalled, "One thing I remember is out working in the garden.

I remember Dad making a sun dial and a scarecrow, and all

those kinds of things. That was in El Cerrito." Alice

remembered holding Dad's little finger when she had to cross

the street, him calling her "Sis", and getting piggyback rides

to bed. Alice recalled, "When I was growing up Dad took care

of all the scary things for me. He'd squish all the bugs. One

time I opened the back door, and found a snake curled up,

'smiling' at me. I screamed, and ran into the house. Then I

watched through the window, as Dad saved me by chopping up the

snake with a hoe." Raymond remembered going to bed, and giving

his Dad a hug, and being fascinated by his whiskers. Raymond

was also fascinated by Jim's tools. Unfortunately, sometimes

his fascination would lead him to wander off with the tools,

and then forget where he left them. A frantic search would

then ensue. It was at the house on Beth Drive that Jim built a

house for the family pet, a duck named Herkimer. He built a

little house with a ramp leading down into a "pond" - one of

the kids' old wading pools.

Bill

shared some early memories of his Dad. The first was when his

dad spanked him. He thought that he had the world's biggest

hands! He also remembers giving his dad a hug, and feeling his

face, and thinking, "Oooh, scratchy!" He was fascinated by his

dad's magnifying glasses, which Jim always had at the table

for closeup work. He also remembered his dad amazing him with

a small wood pipe cutout he made, which could do balancing

tricks with a belt.

The late

60s were tough years for Jim. The opening of another ERMA

center in Los Angeles meant long weeks away from his family.

His family became used to seeing him off at the airport.

Charlie said, "I remember going to the airport, and seeing the

Lockheed Electras he was always coming and going in. The

planes he took up and down to Los Angeles were all turbo

props." In January Jim and Alice flew to Los Angeles to pick

up a 1955 orange Mercury that had belonged to Beulah's father.

While they were there Jim got a phone call, saying that his

mother had a stroke, and passed away. Jim and Alice hurriedly

returned home for her funeral. Later that year, in December,

Jim's brother Tom died.

Jim

shared his love of chemistry with his family. His children

remembered watching as he set off homemade gopher bombs to

chase the rodents from their lawn. Alice recalls that one

Christmas Jim made a Christmas tree out of wire, and then put

it in a chemical solution. She watched in fascination as

silver icicles appeared on the tree. Jim also helped Alice get

an A on a sixth grade science assignment. He helped her gather

42 different chemical elements which they put in little

plastic bags, and stapled on a chart. She was the only one in

her class to have uranium, and classmates had fun playing with

the silvery mercury she brought in. Her teacher was

overwhelmed! Bill remembers his dad trying to make a nugget of

gold. Jim took old electronic parts which had a tiny amount of

gold in them, and tried to refine the gold out of them to make

a small nugget.

The

children were also amazed by their Dad's ability to do things

right. He could learn anything by reading a book - painting,

wallpapering, tiling. He always did things meticulously. Alice

remembers, "He didn't just slap paint on the wall. He would

tape the windows, and prepare the wall. He always took the

time to do things right. Later he wallpapered Michelle's room

for me. It was perfect - all the patterns were lined up

correctly. He taught me how to wallpaper, but I can't do it as

well as he could."

Alice

remembers, "I guess my favorite memory was the Gold and Green

Ball. The graduating girls were supposed to waltz with their

fathers. Dad didn't know how to waltz, and hated to be looked

at, but there we were, doing a two step around the dance

floor. I think my proudest moment was when I got a scholarship

to Berkeley, and he said, "She's got my brains."

RETIREMENT

Jim's

co-workers at the bank had many positive things to say about

Jim. Many programmers got their start under his tutelage. Tony

Russo remembered that in a tough, competitive business world,

Jim was exemplary for his integrity. Jim retired and tried to

take things easy. He went to lunch with old work friends like

Herm Moss. His first project was a brick edging lining the

front walkway. It took months and months to build, but when it

was done it was perfect.

Jim and

Beulah took a trip in 1978 to pick up Raymond from his mission

in Germany. They took a cruise down the Rhine River. Later,

Charlie sent them on a trip to Hawaii. Jim enjoyed reliving

these trips through photos, videotapes, and music.

Jim's

first grandchild, Michelle Anne Boyd, was born in 1976. After

that, Adam Richard Boyd was born in 1979, then Megan Jean

Carey, Michael Carey, Kyle Carey, and Kira Carey. His last

grandchild, Daniel Carey was born in 1992. Michelle and

Adam remember these things about their Grandpa:

Michelle: "Grandpa would set up the ball clock to

entertain us. He also let me use his pedometer, and bounce on

the trampoline and measure it in miles. If I ever needed a

pencil or paper, all I needed to do was look where he sat. He

could do all sorts of things, like put up bricks. He could

paint and do tile. Grandpa and Grandma were funny. They would

always go together in the car, and argue about how to get

there, and where to go - any little detail. He liked to eat

Laura Scudder peanut butter, A&W root beer, and

weird-looking soups, like split pea and tomato."

Adam: "He liked to read, sleep, and play with the

remote control. When I was in the back room, he always used to

come in and show me things, like that little compass. I

remember he taught me how to lay bricks."

Jim like

to read and study many things. He seemed to know all kinds of

interesting and obscure facts. When Alice was working at the

library, and was stumped by the question, "What's the proposed

state fish of Hawaii?", she called him. He said, "Why that's

the Humu-humu-nuka-nuka-apuaa." He loved to study maps, and do

calculations on his ever-present yellow legal pads. His

grandchildren always knew that if they were stumped on a

homework question, they could call Grandpa for the answer.

Alice also enjoyed talking with her father about her

discoveries when she worked on their common Irish ancestry. He

would help translate Latin passages for her, and tell her

stories about his parents.

Jim also

loved gadgets. He loved to put together Heathkits. He owned a

variety of calculators for doing his calculations. Charlie

could remember a gadget from his childhood, "Dad had a puptent

kind of antenna. It was an arrangement of sticks, about the

size of a box kite, and triangular shape. It had copper wire

wrapped around it. You could see one channel in one direction,

and turn it another way for another channel. He ended up

putting it up in the attic, and pointing it some way that

worked best for most things." Jim had a scanner he would

listen to, and then call Bill and warn him about things going

on in his area. Jim would amuse his youngest grandson, Daniel,

by showing him his talking clock, or making the bird come out

of the cuckoo clock. He loved to show visitors his latest

gadgets.